30 SECOND NOTES:Romeo & Juliet is Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s first masterpiece, written when he was 29 and just recovering from a recent broken affair of the heart. The young composer managed to capture the passion of Shakespeare’s timeless tragedy as well as his own romantic emotions within the tone poem’s brilliantly orchestrated and carefully calculated formal structure. Maurice Ravel said, “I felt that in the Concerto in G I had expressed myself most completely, and that I had poured my thoughts into the exact mold I had dreamed.” In addition to the craftsmanship, glittering orchestral palette, and typically French élan of all his compositions, the Concerto in G also drew on an American export then sweeping Europe — Le Jazz Hot — and paid homage both to the music of George Gershwin, whom Ravel had met several years before, and to Ravel’s recent tour of the United States. Jean Sibelius was a Finnish hero. His earliest orchestral works, capped in 1899 by Finlandia, were inspired by the Kalevala, the tales of Finland’s mythical heritage, and so inflamed the Finns’ patriotism that the occupying Russians forbid its performance. Sibelius’ magnificent Symphony No. 2 of 1902 was both a triumph at home and a continuing notice to the world of Finland’s quest for self-governance, which was finally realized in 1917.

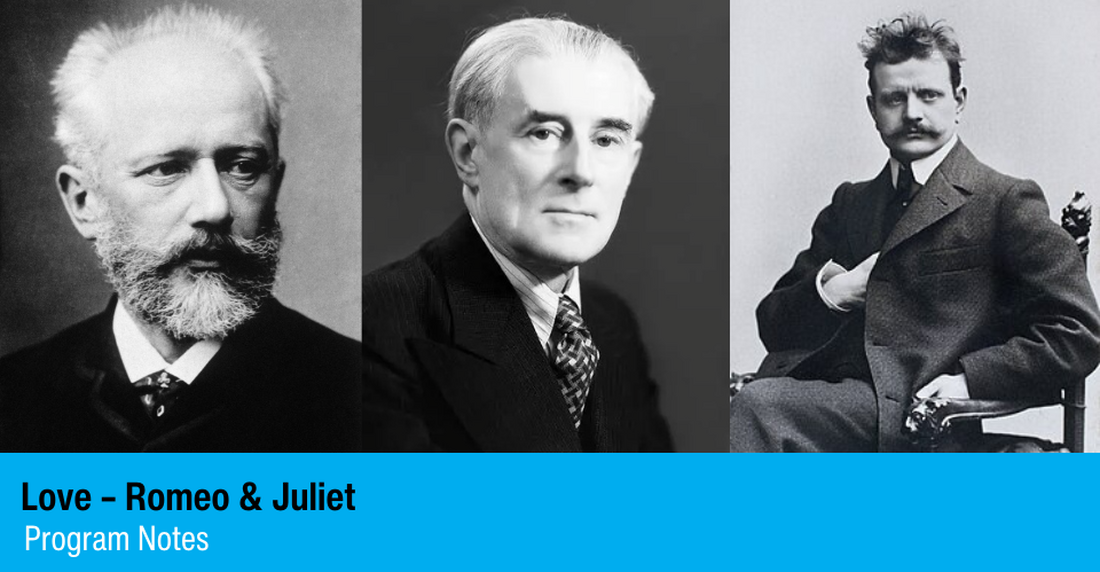

Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky

Born May 7, 1840 in Votkinsk;

died November 6, 1893 in St. Petersburg.

ROMEO & JULIET, FANTASY-OVERTURE

- First performed on March 16, 1870 in Moscow, conducted by Nikolai Rubinstein.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on April 18, 1948 with Frank Noyes conducting. Seven subsequent performances occurred, most recently on February 12 & 13, 2011 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 19 minutes)

Tchaikovsky wrote Romeo & Juliet in 1869, when he was 29. It was his first masterpiece. He was emotionally primed for his musical portrayal of the star-crossed lovers by his own romantic misadventure of the preceding year, when he had been infatuated with the French opera singer Désirée Artôt, who was enjoying a considerable vogue in St. Petersburg in 1868, and felt strongly enough to consider marrying her. He carried his suit to this lady whom he described to his brother Modeste as possessing “exquisite gesture, grace of movement, and artistic poise,” but she apparently regarded his proposal of marriage somewhat less seriously than he did — within a month she married another opera singer, Padilla y Ramos, in Warsaw. Tchaikovsky never revealed exactly how deep a wound this affair inflicted, but he did make a point of recounting their later meetings in his personal letters, always praising her beauty and artistry. His torch for Artôt may never have been fully extinguished. While the Artôt episode was probably not directly responsible for the creation of Romeo & Juliet, it was an important emotional component of Tchaikovsky’s personality at the time. The composer, a firm believer that Fate seeks to dampen man’s every happiness, could easily have drawn a parallel between his personal loss and the tragedy of Shakespeare’s drama.

Tchaikovsky’s Romeo & Juliet is among the most successful reconciliations in the orchestral repertory of a specific literary program with the requirements of logical musical structure. The work is in carefully constructed sonata form, with introduction and coda. The slow opening section, in chorale style, depicts Friar Lawrence. The exposition (Allegro giusto) begins with a vigorous, syncopated theme depicting the conflict between the Montagues and the Capulets. The melee subsides and a lyrical theme (used here as a contrasting second subject) is sung by the English horn to represent Romeo’s passion; a tender, sighing phrase for muted violins suggests Juliet’s response. A stormy development section utilizing the driving main theme and music from the introduction denotes the continuing feud between the families and Friar Lawrence’s urgent pleas for peace. The crest of the fight ushers in the recapitulation, which is a considerably compressed version of the exposition. Juliet’s sighs again provoke the ardor of Romeo, whose motive is given a grand setting that marks the work’s emotional high point. The tempo slows, the mood darkens, and the coda emerges with the sense of impending doom. The themes of the conflict and of Friar Lawrence’s entreaties sound again, but a funereal drum beats out the cadence of the lovers’ fatal pact. Romeo’s motto appears for a final time in a poignant transformation before the closing woodwind chords evoke visions of the flight to celestial regions.

The score calls for pairs of woodwinds plus piccolo and English horn, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, harp and the usual strings, consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

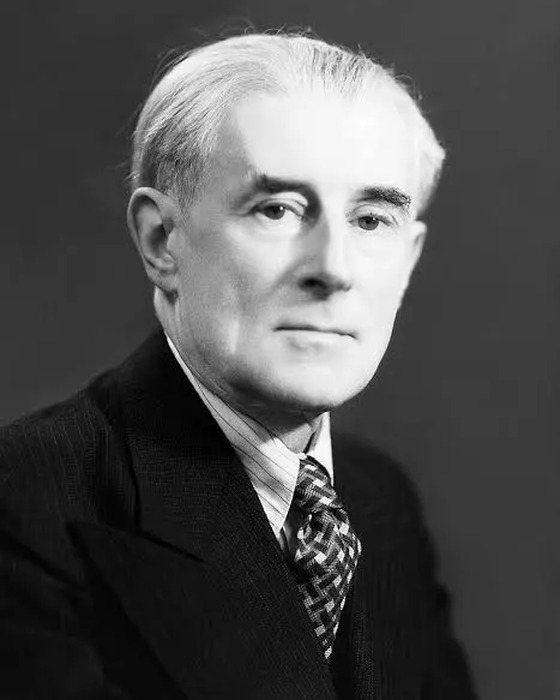

MAURICE RAVEL

Born March 7, 1875 in Ciboure, Basses-Pyrénées, France;

died December 28, 1937 in Paris.

PIANO Concerto in G MAJOR

- First performed on January 14, 1932 in Paris, with Marguerite Long as soloist and the composer conducting.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on October 4, 1975 conducted by Yuri Krasnapolsky with David Bar-Illan as soloist. Two subsequent performances occurred, most recently on May 3 & 4, 2008 conducted by Joseph Giunta with Christopher O’Riley as soloist.

(Duration: ca. 22 minutes)

Ravel’s tour of the United States in 1928 was such a success that he began to plan for a second one as soon as he returned to France. With a view toward having a vehicle for himself as a pianist on his return visit, he started work on a concerto in 1929, perhaps encouraged by the good fortune that Stravinsky had enjoyed concertizing with his Concerto for Piano & Winds and Piano Capriccio earlier in the decade. Both to polish his keyboard technique and to extend his repertory — he seems to have harbored a desire to be a concert virtuoso into his last years — Ravel spent much time and effort in those months practicing the works of Liszt and Chopin. Many other projects pressed upon him, however, not the least of which was a commission from the pianist Paul Wittgenstein, who had lost his right arm in the First World War, to compose a piano concerto for left hand alone. Ravel set aside the tour concerto for nine months to work on Wittgenstein’s commission and the Concerto in G was not completed until 1931.

Ravel was so excited by the fine reception given to the Concerto at its first performance, in January 1932, that he wanted to take it on an around-the-world tour with Marguerite Long, the soloist at the premiere. They did not get quite that far, but they did have a four-month tour that spring that went to several cities in central Europe and England. Despite Ravel’s initial enthusiasm for traveling with the Concerto, however, the rigors of the trip seem to have taken a heavy toll on his always-delicate health, and later that summer he started suffering from a number of medical setbacks that culminated the following year in the discovery of a brain tumor. His health never returned, and the Concerto in G was his last major composition.

The Concerto’s sparkling first movement opens with a bright melody in the piccolo that may derive from an old folk dance of the Basque region of southern France, Ravel’s birthplace. There are several themes in the exposition: the lively opening group is balanced by another set that is more nostalgic and bluesy in character. The development section is an elaboration of the lively opening themes, ending with a brief cadenza in octaves to link to the recapitulation. The lively themes are passed over quickly, but the nostalgic melodies are treated at some length. The jaunty vivacity of the beginning returns for a dazzling coda.

When Ravel first showed the manuscript of the Adagio to Marguerite Long, she commented on the music’s effortless grace. The composer sighed, and told her that he had struggled to write the movement “bar by bar,” that it had cost him more anxiety than any of his other scores. The movement begins with a long-breathed melody for solo piano over a rocking accompaniment. The central section does not differ from the opening as much in melody as it does in texture — a gradual thickening occurs as the music proceeds. The texture then becomes again translucent, and the opening melody is heard on its return in the plaintive tones of the English horn.

The finale is a showpiece for soloist and orchestra that evokes the world of jazz. Trombone slides, muted trumpet interjections, shrieking exclamations from the woodwinds abound. The episodes of the form tumble continuously one after another on their way to the work’s abrupt conclusion.

The score calls forpiccolo, flute, oboe, English horn, E-flat clarinet, B-flat clarinet, two bassoons, two horns, trumpet, trombone, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle, woodblock, tam-tam, whip, harp and the usual strings.

JEAN SIBELIUS

Born December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland;

died September 20, 1957 in Järveenpää, Finland.

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43

- First performed on March 8, 1902 in Helsinki, conducted by the composer.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on May 8, 1949 with Frank Noyes conducting. Four subsequent performances occurred, the most recent on April 18 & 19, 2015 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 46 minutes)

At the turn of the 20th century, Finland was experiencing a surge of nationalistic pride that called for independence and recognition after eight centuries of domination by Sweden and Russia. Jean Sibelius became imbued with the country’s spirit, lore and language, and several of his early works — En Saga, Kullervo, Karelia and Finlandia — earned him a hero’s reputation among his countrymen. Sibelius became an emblem of his homeland in 1900 when conductor Robert Kajanus and the Helsinki Philharmonic featured his music on a European tour whose purpose was less artistic recognition than a bid for international sympathy for Finnish political autonomy. The young composer went along on the tour, which proved to be a success for the orchestra and its conductor, for Finland, and especially for Sibelius, whose works it brought before an international audience.

A year later Sibelius was again traveling. Through a financial subscription raised by his friend and wealthy supporter Axel Carpelan, he was able to spend the early months of 1901 in Italy away from the rigors of the Scandinavian winter. So inspired was he by the culture, history and beauty of the sunny south (as had been Goethe and Brahms) that he envisioned a work based on Dante’s Divine Comedy. However, a second symphony to follow the first of 1899 was gestating, and the Dante work was eventually abandoned. Sibelius was well launched on the new Symphony No. 2 by the time he left for home. He made two important stops before returning to Finland. The first was at Prague, where he met Dvořák and was impressed with the famous musician’s humility and friendliness. The second stop was at the June Music Festival in Heidelberg, where the enthusiastic reception given to his compositions enhanced the budding European reputation that he had achieved during the Helsinki Philharmonic tour of the preceding year. Still flush with the success of his 1901 tour when he arrived home, he decided he was secure enough financially (thanks in large part to an annual stipend initiated in 1897 by the Finnish government) to leave his teaching job and devote himself full-time to composition. Though it was to be almost two decades before Finland became independent of Russia as a result of the First World War, Sibelius had come into his creative maturity by the time of the Second Symphony. So successful was the work’s premiere on March 8, 1902 that it had to be repeated at three added concerts to satisfy the clamor to hear Sibelius’ latest creation.

The Second Symphony opens with an introduction in which the strings present a chordal motive that courses through and unifies much of the first movement. A bright, folk-like strain for the woodwinds and a hymnal response from the horns constitute the opening theme. The second theme exhibits one of Sibelius’ most characteristic constructions — a long-held note that intensifies to a quick rhythmic flourish. This theme and a complementary one of angular leaps and unsettled tonality close the exposition and figure prominently in the ensuing development. A stentorian brass chorale closes this section and leads to the recapitulation, a compressed restatement of the earlier themes.

The second movement, though closely related to sonatina form (sonata without development), is best heard as a series of dramatic paragraphs whose strengths lie not just in their individual qualities but also in their powerful juxtapositions. The opening statement is given by bassoons in hollow octaves above a bleak accompaniment of timpani with cellos and basses in pizzicato notes. The upper strings and then full orchestra take over the solemn plaint, but soon inject a new, sharply rhythmic idea of their own that calls forth a halting climax from the brass choir. After a silence, the strings intone a mournful motive which soon engenders another climax. A soft timpani roll begins the series of themes again, but in expanded presentations with fuller orchestration and greater emotional impact.

The third movement is a three-part form whose lyrical, unhurried central trio, built on a repeated note theme, provides a strong contrast to the mercurial surrounding scherzo. The slow music of the trio returns as a bridge to the sonata-form closing movement, which has a grand sweep and uplifting spirituality that make it one of the last unadulterated flowerings of the great Romantic tradition.

The score calls for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and the usual strings.