Read about the music and composers featured in Masterworks 4: Immortal Beloved on January 29 & 30, 2022.

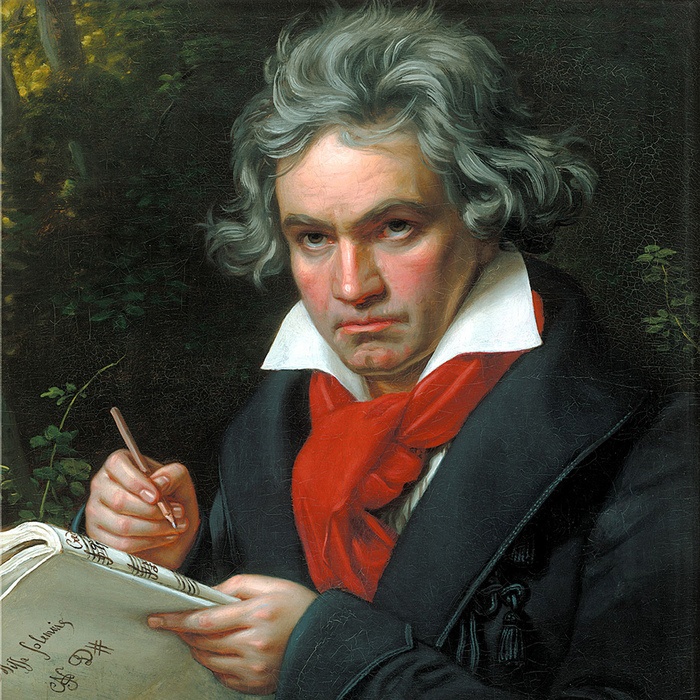

Ludwig van Beethoven, a confirmed and cantankerous bachelor though he wanted it to be otherwise, wrote only three known love letters in his life, his only communication to a woman in which he used the familiar “du” form of address throughout. Dated “Monday, 6 July” but without a year, it was never posted and turned up among his papers after his death. The salutation was to the “Unsterbliche Geliebte” — “The Immortal Beloved.” The intended recipient has never been indisputably identified, but there are two leading candidates. One, Antonie Brentano, daughter of Joseph Melchior von Birkenstock, a trusted advisor to Empress Maria Theresia, married the Frankfurt businessman Franz Brentano in 1798, when she was eighteen, but returned to Vienna in 1809 to nurse her dying father. Beethoven was introduced to the family in May 1810 and during the following years apparently conceived a passion for Antonie. The other lady, Josephine von Brunswick, was a sister of Count Franz von Brunswick, an important patron during Beethoven’s early years in Vienna. The question remains unresolved.

DOBRINKA TABAKOVA

Born January 1, 1980 in Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

DAWN FOR SOLO VIOLIN & CELLO WITH STRING ORCHESTRA

• First performed on February 25, 2007 in Kronberg, Germany by the Kremerata Baltica, with violinist Gidon Kremer and cellist Kristine Blaumane as soloists.

• These concerts mark the first performance of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 8 minutes)

Dobrinka Tabakova was born in 1980 in the ancient Bulgarian city of Plovdiv, founded in the Fourth Century BCE by Philip II of Macedon, father of Alexander the Great. Since she was eleven, however, Tabakova has lived in London, where her parents, both eminent medical physicists and music lovers, moved to accept positions at King’s College Hospital. Tabakova’s musical talent developed early and at fourteen she won the Jean-Frederic Perrenoud Prize of the Fourth International Competition of Music in Vienna. She earned Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama and a Doctorate at King’s College, London, and has made her career exclusively as a composer. Her works have been performed widely in Britain and Europe and increasingly overseas. Tabakova has fulfilled many commissions, held several residencies, including with the BBC Concert Orchestra since 2017, and received awards and commissions from the BBC, Royal Philharmonic Society, Vienna International Music Competition, Queen’s Golden Jubilee and Amsterdam Sinfonietta; her debut profile album, String Paths (ECM Records), was nominated for a Grammy in 2014.

Tabakova composed Dawn in 2007 for the 10th anniversary of the Kremerata Baltica and the 60th birthday of its founder and leader, violinist Gidon Kremer; it was premiered on February 25, 2007 at Kronberg Castle, north of Frankfurt. Tabakova wrote, “Dawn is the first of three pieces making up the triptych Dawn–Day–Dusk. It represents sunrise with low, rich chords in the orchestra, which ascend throughout the triptych with decorated violin and cello solos.”

The score calls for solo violin, solo cello and the usual strings consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born December 16, 1770 in Bonn;

died March 26, 1827 in Vienna.

ALLEGRETTO FROM SYMPHONY NO. 7 IN A MAJOR, OP. 92

• First performed on December 8, 1813 in Vienna, conducted by the composer.

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on January 14, 1962 with Frank Noyes conducting. Subsequently performed eight times, most recently on March 24 & 25, 2018 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 9 minutes)

In the autumn of 1813, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, the inventor of the metronome, approached Beethoven with the proposal that the two organize a concert to benefit the soldiers wounded at the recent Battle of Hanau — with, perhaps, two or three repetitions of the concert to benefit themselves. Beethoven was eager to have the as-yet-unheard Symphony No. 7 composed the preceding year performed, and thought the financial reward worth the trouble, so he agreed. The concert consisted of this “Entirely New Symphony” by Beethoven, marches by Dussek and Pleyel performed on a “Mechanical Trumpeter” fabricated by Mälzel, and an orchestral arrangement of Wellington’s Victory, a piece Beethoven had concocted the previous summer for yet another of Mälzel’s musical machines, the “Panharmonicon.” The evening was such a success that Beethoven’s first biographer, Anton Schindler, reported, “All persons, however they had previously dissented from his music, now agreed to award him his laurels.” In form, the Allegretto of the Symphony No. 7 is a series of variations on the heartbeat rhythm of its opening measures. In spirit, however, it is more closely allied to the austere chaconne of the Baroque era than to the light, figural variations of Classicism.

The score calls for flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons in pairs, two horns, two trumpets, timpani and the usual strings.

“MOONLIGHT SONATA” FROM PIANO SONATA NO. 14 IN C-SHARP MINOR, OP. 27, NO. 2

• First performance unknown.

• These concerts mark the first performance of this piece on a Des Moines Symphony program.

(Duration: ca. 6 minutes)

Beethoven fell in love many times, but never married. (The thought of Beethoven as a husband threatens the moorings of one’s presence of mind!) The source of his infatuation in 1801, when he was thirty and still in hope of finding a wife, was the Countess Giulietta Guicciardi, who was thirteen years his junior, rather spoiled, and reportedly something of a vixen. She seems to have been flattered by the attentions of the famous musician, but probably never seriously considered his intimations of marriage; her social station would have made wedlock difficult with a commoner such as Beethoven. For his part, Beethoven was apparently thoroughly under her spell at the time, and mentioned his love for her to a friend as late as 1823, though by then she had been married to Count Wenzel Robert Gallenberg, a prolific composer of ballet music, for two decades. A medallion portrait of her was found among Beethoven’s effects after his death. The C-sharp minor Sonata was contemporary with the love affair with Giulietta and dedicated to her upon its publication in 1802, but the precise relationship of the music’s nature and the state of Beethoven’s heart must remain unknown; he never indicated that the piece had any programmatic intent. It was not until five years after his death that the work’s passion and emotional intensity inspired the Romantic German poet and music critic Ludwig Rellstab (whose verses Schubert set in 1828 as the first seven numbers of his Schwanengesang) to describe the Sonata in terms of “a vision of a boat on Lake Lucerne by moonlight,” a sobriquet that has since inextricably attached itself to the music.

In noting the experimental nature of the work’s form, Beethoven indicated that it is a sonata “in the manner of a fantasy” (Sonata quasi una Fantasia). The Classical model for the instrumental sonata comprised three independent movements: a fast movement in sonata form; an Adagio or Andante arranged as a variations or three-part structure; and a closing rondo in galloping meter. In the “Moonlight” Sonata, Beethoven altered the traditional fast–slow–fast sequence in favor of an innovative organization that shifts the expressive weight from the beginning to the end of the work, and made the cumulative effect evident by instructing that the movements be played without pause. Instead of opening with a large symphonic-style, sonata-form essay, the “Moonlight” initially falls upon the listener with a somber, minor-mode Adagio of great introspection. Next comes a subdued scherzo and trio whose delicacy is undermined by its off-beat syncopations. The expressive goal of the Sonata is achieved with its closing movement, a powerful sonata-form essay filled with tempestuous feeling and dramatic gesture.

The score calls for solo piano.

AUGUSTA HOLMÈS

Born December 16, 1847 in Paris;

died January 28, 1903 in Paris.

“LA NUIT ET L’AMOUR” (“NIGHT AND LOVE”) FROM LUDUS PRO PATRIA (“PATRIOTIC GAMES”)

• First performed on March 4, 1888 in Paris, conducted by Jules Auguste Garcin.

• These concerts mark the first performance of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 6 minutes)

Augusta Holmès, born in Paris in 1847, was a woman of the Victorian Age, though hardly representative of that era’s (not fully justified) prim and proper image of femininity — her birth may have occurred out of wedlock; she never married, but had five children by another woman’s husband; she defied her parents’ express wishes by becoming a composer and made a successful career through sheer will-power and persistence in a society that forbade women having a conservatory education; she served as a nurse in the Franco-Prussian War; the giant Ode Triomphale she was commissioned to write for the 1889 Exposition Universelle, staged in Paris in celebration of the centenary of the storming of the Bastille, required 1,200 performers and many thought it inappropriately “virile” and “masculine.” Camille Saint-Saëns observed, “Women have no idea of obstacles, and their willpower breaks all barriers. Mademoiselle Holmès is a woman, an extremist.” She was also a beauty. Saint-Saëns himself claimed that “we are all of us in love with her,” and proposed to her several times and also dedicated to her his 1871 tone poem, Rouet d’Omphale (“Omphale’s Spinning Wheel”). The painter Georges Clairin said she was “not so much a woman as a goddess,” Stéphane Mallarmé made her the subject of two short poems, and César Franck, with whom she studied privately, was rumored to have been inspired by Augusta to compose his passionate Quintet for Piano & Strings. (Franck’s shrewish wife denounced the piece to anyone who would listen.) Augusta Holmès was not a conventional 19th-century woman, but she was a pioneer in asserting the creative, intellectual and social qualities of her gender.

Augusta Holmès was born in 1847 into the family of an Irish military officer who had retired to a small town in France and a French woman of Scottish-Irish descent; the couple had been married twenty years before Augusta came along. Captain Holmes was scholarly and his wife was skilled in poetry and painting, and they moved to Paris soon after the wedding to participate in the city’s rich cultural life. Among their Parisian friends was the poet Alfred de Vigny, who became close enough to the couple that they named him Augusta’s godfather and was, perhaps, even her biological father. (Augusta did little to dispel the rumor.) Despite Madame Holmes’ artistic leanings, she forbade her daughter to pursue her interest in music so decisively that the girl once stabbed herself with a small dagger.

It was not until her mother died, when Augusta was eleven (by which time her father was ready to give in to his headstrong daughter), that she began piano and voice lessons and serious music study. Within two years, she was an accomplished pianist and singer and had begun to compose (and, in her spare time, paint and write poetry in the four languages she spoke). She became a French citizen in 1871 (and added an accent grave to her family name), was welcomed into Parisian artistic circles, had her first public performances in 1873, began studying with Franck in 1875, and devoted herself largely to the most ambitious musical genres in defiance of the prevailing notion that “lady composers” should confine themselves to songs and salon pieces — her first major work was the 1875 opera Héro et Leandre, followed by two others, all to her own librettos (La Montaigne Noire was produced at the Paris Opéra in 1895), a dozen large-scale secular cantatas, four symphonic poems, many songs, choruses and piano pieces. In 1869, she met the poet Catulle Mendès, with whom she shared a passion for Wagner, and traveled with him and his wife the following year to meet the composer at his home near Lucerne. Soon thereafter, she and Mendès began the twenty-year affair that yielded their five children. (In sort of karmic recompense, Madame Mendès later had a brief affair with Wagner.) After their separation, Holmès continued to compose and teach until her death in 1903 at the age of 55. Streets in Paris and Versailles, her childhood home, were named in her honor.

Ludus pro Patria (“Patriotic Games”) was the last of four works Holmès composed on nationalistic themes during the decade after 1878, perhaps her delayed response to the French defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-1871 — Lutèce (1878, titled after the ancient Roman name for Paris), Irlande (“Ireland,” 1882, after her ancestral homeland), Pologne (“Poland,” 1883) and Ludus pro patria (1888). Ludus pro Patria, a “symphonic ode” for speaker, choruses and orchestra to her own text, was inspired by and named for a painting by the French artist Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. The painting is now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York City, whose web site gives this description: “Puvis’ evocation of ancient France shows young athletes training with pikes (piques in French), the traditional weapon of the Picardy region and reputedly the origin of the province’s name. This work is a replica, reduced in size, of the central panel of a mural that Puvis completed in 1882 and installed in the Musée de Picardie in Amiens. The exhibition and sale of such ‘reductions’ helped publicize the artist’s monumental decorative commissions and boost his income.” Ludus pro Patria was so successful at its premiere, at the Société des Concerts du Conservatoire on March 4, 1888, that it had to be repeated the following week.

Holmès headed La Nuit e L’Amour (“Night and Love”), the work’s instrumental interlude, with the following verses: “Love! Divine word! Creator of worlds!/Love! Inspiration of fruitful ecstasy!/Love! Conqueror of Conquerors!”

The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, two trumpets, timpani, harp, and the usual strings.

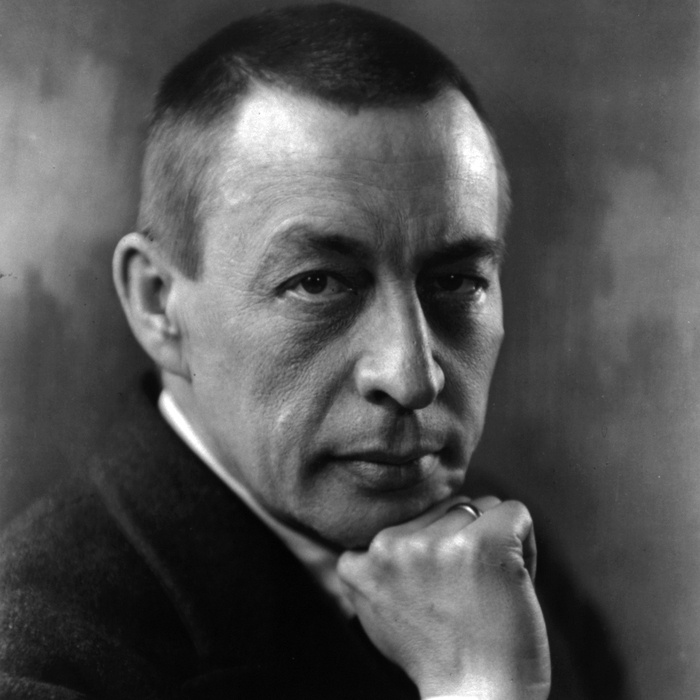

SERGEI RACHMANINOFF

Born April 1, 1873 in Oneg (near Novgorod), Russia;

died March 28, 1943 in Beverly Hills, California.

PIANO CONCERTO NO. 3 IN D MINOR, OP. 30

• First performed on November 28, 1909 in New York, conducted by Walter Damrosch with the composer as soloist.

• First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on November 23, 1958 with Frank Noyes conducting and Moura Lympany as soloist. Subsequently performed seven times, most recently on May 12 & 13, 2012 with Joseph Giunta conducting and Barry Douglas as soloist.

(Duration: ca. 40 minutes)

The worlds of technology and art sometimes brush against each other in curious ways. In 1909, it seems, Sergei Rachmaninoff wanted one of those new mechanical wonders — an automobile. And thereupon hangs the tale of his first visit to America.

The impresario Henry Wolfson of New York arranged a thirty-concert tour for the 1909-1910 season for Rachmaninoff so that he could play and conduct his own works in a number of American cities. Rachmaninoff was at first hesitant about leaving his family and Russian home for such an extended overseas trip, but the generous financial remuneration was too tempting to resist. With a few tour details still left unsettled, Wolfson died suddenly in the spring of 1909, and the composer was much relieved that the journey would probably be cancelled. Wolfson’s agency had a contract with Rachmaninoff, however, and during the summer finished the arrangements for his appearances so that the composer-pianist-conductor was obliged to leave for New York as scheduled. Trying to look on the bright side of this daunting prospect, Rachmaninoff wrote to his long-time friend Nikita Morozov, “I don’t want to go. But then perhaps, after America I’ll be able to buy myself that automobile.... It may not be so bad after all!” It was for the American tour that Rachmaninoff composed his Third Piano Concerto.

The D Minor Concerto consists of three large movements. The first is a modified sonata form which begins with a haunting theme, recalled in the later movements, that sets perfectly the Concerto’s mood of somber intensity. The espressivo second theme is presented by the pianist. The development section is concerned mostly with transformations of fragments from the first theme. A massive cadenza, separated into two parts by the recall of the main theme by the woodwinds, leads to the recapitulation. The second movement, subtitled Intermezzo, is a set of free variations with an inserted episode. The finale is in three large sections. The first part has an abundance of themes that Rachmaninoff skillfully derived from those of the opening movement. The relationship is further strengthened in the finale’s second section, where both themes from the opening movement are recalled in slow tempo. The pace again quickens, and the music from the first part of the finale returns with some modifications. A brief solo cadenza leads to a dazzling coda.

The score calls for flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons in pairs, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, bass drum, crash cymbals, snare drum and the usual strings.