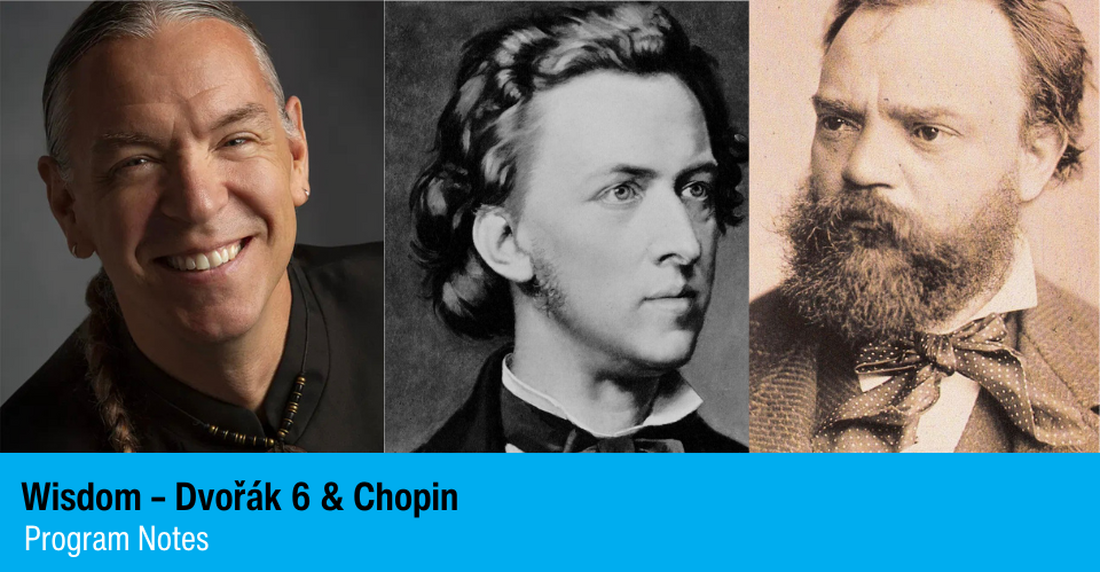

30 SECOND NOTES: Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate, a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation and an inductee into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame, is among the growing cohort of Indigenous composers whose works meld traditional native elements with European forms and styles. Chokfi’, based on a melody of the Muscogee Creek Nation in Oklahoma, “is the Chickasaw word for rabbit,” Tate explained, “who is an important legendary trickster within Southeast American Indian cultures.” Though Frédéric Chopin was one of the most influential pianists of the 19th century, he disliked performing in public, and in 1835, after leaving Warsaw for Paris, abandoned the concert stage in favor of teaching and appearing at private salons. His handful of works with orchestra, including the Piano Concerto No. 2 of 1829, are therefore creations of his early years, when he was still trying to establish his reputation with the music-loving public. The reception of the Symphony No. 6 by Antonín Dvořák was buoyed by the international success of his recent Slavonic Dances, and was also an immediate hit. “No sooner was it published,” wrote his biographer Karel Hoffmeister, “than it made its way abroad to Leipzig, Rostock, Graz, Cologne, Frankfurt, Boston and New York [in 1883; Dvořák conducted it there in 1892, during the first year of his American residency]. The Sixth Symphony finally attracted even the reserved public of England,” where Dvořák became the most acclaimed European composer since Mendelssohn and was made a doctor honoris causa by Cambridge University. 32nd Notes

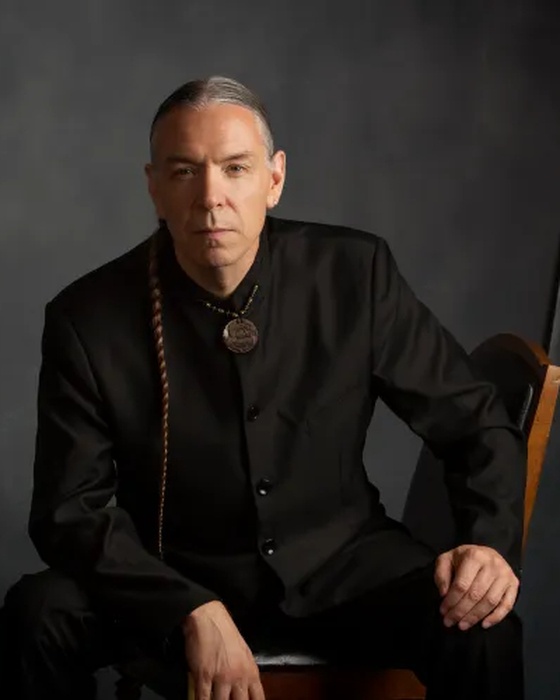

Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate

Born on July 25, 1968 in Norman, Oklahoma.

CHOKFI’

- First performed on May 6, 2018 in Oklahoma City by the Oklahoma Youth Orchestra

- These concerts mark the first performances of this piece by the Des Moines Symphony.

(Duration: ca. 20 minutes)

Jerod Impichchaachaaha’ Tate (“Taloa Ikbi”), born in 1968 at Norman, Oklahoma, is of Chickasaw and Manx descent and a citizen of the Chickasaw Nation. (Mr. Tate’s middle name, Impichchaachaaha’, means “his high corncrib” and is his inherited traditional Chickasaw “house name.” A corncrib is a small hut elevated on stilts off the ground that is used to store corn and other vegetables.) His father, Charles (Chickasaw), was a Tribal Judge and a classically trained pianist and baritone who played at home as well as in professional performance; his mother, Patricia, of Manx–Irish descent, was a professor of dance and a choreographer. Jerod began piano lessons at age eight, announcing to his parents soon thereafter that he was going to be a professional musician. He progressed rapidly as a pianist during his high school years and in 1986 was granted a four-year, full-tuition scholarship to Northwestern University, where he studied with Donald Isaak, participated in master classes with Claude Frank and Eckart Sellheim, and received the Corinne Frada Pick Award as Outstanding Music School Senior. After earning his Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance from Northwestern in 1990, Tate was awarded a full-tuition scholarship to attend the Adamant Music School in Vermont, and was selected to represent the School at its New York City recital series. He went on to complete Master’s Degrees in piano and composition at the Cleveland Institute of Music, where his principal teachers were Elizabeth Pastor and Donald Erb.

Tate has worked as a pianist/keyboardist, notably on national tours of Les Misérables and Miss Saigon and as accompanist for the Colorado Ballet, Hartford Ballet and other dance companies, but he has devoted himself primarily to creating a distinctive musical voice for Indigenous Americans within Classical traditions with what a critic for the Washington Post called an “ability to effectively infuse classical music with American Indian nationalism.” Early in his career, Tate composed the music for a series titled First Americans Journal produced by Native American Television in Minneapolis, and he has since worked tirelessly as an advocate for Indigenous composers and performers — his works, rooted in Indigenous culture and history with many incorporating existing melodies, have been commissioned and performed by leading orchestras, soloists and ensembles across North America; he has long been involved with the Lakota Music Project, the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra’s flagship Bridging Cultures Program; he implemented the First Nations Composers Initiative to commission works from North American Indian composers; he was the founding composition instructor at the Chickasaw Summer Arts Academy in Oklahoma and has taught composition to American Indian students in Minneapolis, Toronto and on many reservations, as well as at the Grand Canyon Music Festival Native American Composer Apprentice Project; he was Guest Composer/Conductor/Pianist for the San Francisco Symphony’s Currents program Thunder Song: American Indian Musical Cultures; and his music has been featured on the hit HBO series Westworld.

In 2022, Jerod Tate was inducted into the Chickasaw Hall of Fame and also received the Distinguished Alumni Award from the Cleveland Institute of Music; he had served as a Cultural Ambassador for the U. S. Department of State a year earlier. Among Tate’s other honors are appointment as Creativity Ambassador for the State of Oklahoma, an Emmy Award for his work on the Oklahoma Educational Television Authority documentary The Science of Composing, and the 2025 Wise-Hinrichsen Award in Music from the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Tate has taught at Oklahoma City University and in spring 2023 served as Composer-in-Residence at the University of Oklahoma.

The composer wrote, “Chokfi’ (choke-fee) is the Chickasaw word for rabbit, who is an important legendary trickster within Southeast American Indian cultures. Inspired by a commission for the Oklahoma Youth Orchestra, I decided to create a character sketch that would be both fun and challenging for young musicians. Different string and percussion techniques and colors represent the complicated and diabolical personality of this rabbit–person. In honor of my Muscogee Creek friends of Oklahoma, I have incorporated a popular tribal church hymn as the work’s melodic and musical base.”

The score calls for two flutes, alto flute, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, trumpet, trombone, bass drum, cymbals, field drum, tom-toms, bongos, chimes, crotales, tam-tam, maracas and the usual strings consisting of first violins, second violins, violas, violoncellos and double basses.

Frédéric Chopin

Born February 22, 1810 in Zelazowa-Wola (near Warsaw), Poland;

died October 17, 1849 in Paris.

Piano Concerto No. 2 in F minor, Op. 21

- First performed on March 17, 1830 in Warsaw, with the composer as soloist.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on April 18, 1948 with Frank Noyes conducting and Menahem Pressler as soloist. Three subsequent performances occurred, most recently on March 28 & 29, 2015 with Jia Cheng Xiong as soloist and Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 34 minutes)

During his student days at the Warsaw Conservatory in the late 1820s, Chopin met a comely young singer named Constantia Gladowska and for the first time in his life, fell in love. In his biography of the composer, Casimir Wierzynski wrote, “Constantia was considered one of the school’s best pupils, and also said to be one of the prettiest. Her regular, full face, framed in blond hair, was an epitome of youth, health and vigor, and her beauty was conspicuous in the Conservatory chorus. The young lady, conscious of her charms, was distinguished by ambition and diligence in her studies. She dreamed of becoming an opera singer....” Chopin followed Constantia to her performances and caught glimpses of her when she appeared at the theater or in church, but he never approached her. His love manifested itself in giddily immature ways. He raved about Constantia’s virtues to his friends. He invited one Mrs. Beyer to dinner simply because her given name was the same as that of his beloved. He reported “tingling with pleasure” whenever he saw a handkerchief embroidered with her name. He broke off one of his letters abruptly with the syllable “Con — ,” explaining, “No, I cannot complete her name, my hand is too unworthy.”

After yet another half year of such maudlin goings-on, Chopin finally met — actually talked with — Constantia in April 1830. She was pleasant to him and they became friends, but he was never convinced that she fully returned his love. She took part in his farewell concert in Warsaw on October 11th before he headed west to seek his fame and fortune (he settled in Paris and never returned to Poland), and kept up a correspondence with her for a while through an intermediary. (He felt it improper to write directly to a young woman without her parents’ permission.) Her marriage to a Warsaw merchant in 1832 caused him intense but impermanent grief, which soon evaporated in the glittering social whirl of Paris. The emotional rush of young love Chopin experienced over Constantia played a seminal role in the two piano concertos he wrote in 1829 and 1830, works full of melody and ardent emotionalism that he based on the Romantic piano style of Hummel, Kalkbrenner, Field and Ries rather than on the weightier abstract forms of Beethoven.

In the opening movement of Chopin’s Second Piano Concerto, most of the orchestra’s participation is confined to the introduction, in which are presented the main theme (a rather dolorous tune with dotted rhythms played immediately by violins) and the second theme, a brighter strain given by woodwinds led by the oboe. The piano enters and, with the exception of the orchestral interludes surrounding the development section and the concluding coda, dominates the remainder of the movement. A description of the second movement’s form — three-part (A–B–A) with wide-ranging harmonic excursions in the center section — is too clinical to convey the moonlit poetry and quiet intensity of this beautiful music. The theme of the finale was inspired by the mazurka, the Polish national dance that also served Chopin as the basis for more than fifty stylized compositions for solo piano. The movement’s structure comprises a series of episodes rounded off by the return of the main theme and a cheerful coda.

The score calls for two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, two horns, two trumpets, trombone, timpani and the usual strings.

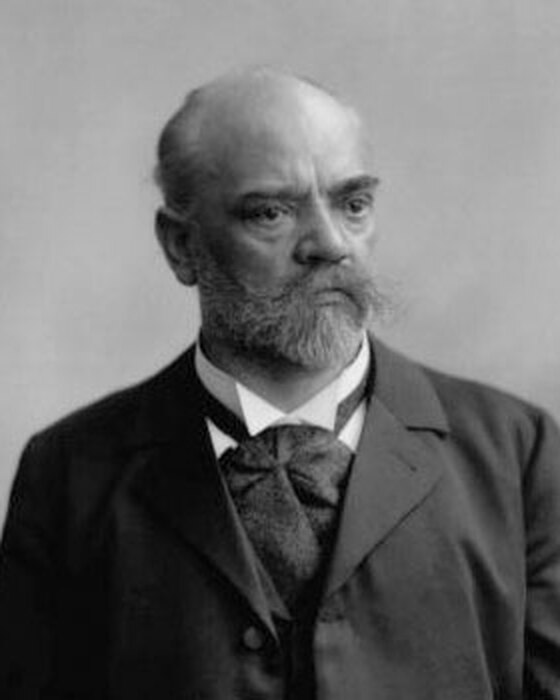

ANTONÍN DVOŘÁK

Born September 8, 1841 in Nelahozeves, Czechoslovakia;

died May 1, 1904 in Prague.

SYMPHONY NO. 6 IN D MAJOR, OP. 60

- First performed on March 21, 1881 in Prague, conducted by Adolf Čech.

- First performed by the Des Moines Symphony on November 18 & 19, 1978 with Yuri Krasnapolsky conducting. One subsequent performance took place on January 31 & February 1, 2009 with Joseph Giunta conducting.

(Duration: ca. 40 minutes)

On November 16, 1879, Dvořák was in Vienna for a performance by the Philharmonic Orchestra and conductor Hans Richter of his Slavonic Rhapsody No. 3, “which was very well received,” he reported. “I had to assure the Philharmonic that I would send them a symphony for the next season.” By 1880, Dvořák had already completed five symphonies — all unpublished — but he did not feel them representative of his best achievements, so he chose to write a new work for Vienna. He could not take up the score until the following August, but once begun he progressed rapidly on it: the sketch was completed in just three weeks and the orchestration in another three (on October 15, 1880), though the composer’s student and biographer Karel Hoffmeister noted that the music “had been slowly maturing in Dvořák’s mind.” Dvořák took the score at once to Vienna to play at the piano for Richter, who, the composer wrote to his friend Alois Goebl, “liked it very much indeed, so that after every movement he embraced me.” The premiere, by Richter and the Philharmonic, was set for December 26.

Shortly before the scheduled premiere date, Richter informed Dvořák that the performance would have to be postponed because there was no time to rehearse and perform the music in the Philharmonic’s busy schedule. The premiere was put off until March, Richter counseling that introducing such a grand and worthy new work during the frivolous carnival season of January and February was inappropriate. Pleading personal and family problems, however, Richter once again canceled the first performance, and Dvořák started to ask some questions of his Viennese friends. It seemed that there was sufficient anti-Czech feeling in those politically volatile days of the Dual Monarchy to cause local resentment against a young Czech composer who would have two important premieres in successive years. Dvořák, who had no taste for such quintessentially Viennese political machinations, gave the honor of the Symphony’s premiere to the Prague Philharmonic and conductor Adolf Cech, with whom he had played in the viola section of the orchestra of the National Provisional Theater in Prague earlier in his career. The work was first heard on March 25, 1881, in Prague. Despite his difficulties in getting the Symphony produced, Richter remained its ardent champion. Dvořák inscribed the score with a dedication to the conductor and sent him one of the first published copies. “On my return from London I find your splendid work awaiting me, whose dedication makes me truly proud,” Richter wrote to Dvořák in January 1882. “Words do not suffice to express my thanks; a performance worthy of this noble work must prove to you how highly I value it and the honor of the dedication.” Richter finally conducted the Symphony on May 15, 1882, in London.

The Symphony No. 6 splendidly combines elements of the symphonic tradition as transmitted by Brahms with what Czech musicologist Otakar Šourek called Dvořák’s “process of idealization” of Czech folk music. This characteristic style of Dvořák, uniting two great streams of concert and vernacular music, richly illumines the Symphony’s opening movement. The influence of Brahms (particularly of his Second Symphony of 1878) is clear in the music’s sylvan sonorities, motivic development and careful control of the ebb and flow of the lines of tension, while the folk quality is heard in the tunefulness of the themes and the many harmonic plangencies. Following the first movement are a lovely Adagio and a fiery Furiant, filled with the same powerful shifting accents borrowed from Bohemian dance that enliven so many of the Slavonic Dances. The bracing last movement, according to Hans-Hubert Schönzeler, “is the most convincing finale Dvořák ever wrote.”

The score calls for flutes, oboes, clarinets and bassoons in pairs plus piccolo, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and the usual strings.